Practicing any skill, be it the piano, math, reading, or anything we are trying to get better at, requires us to think deeply and focus our minds on the task at hand.

Internal distractions are thoughts that pop into your mind that take your attention away from what you are doing. Sometimes the thoughts are helpful but sometimes they aren’t… and when they aren’t, they can quickly escalate into more thoughts and even result in physical reactions from our bodies (for example, cold hands, racing heart, butterflies).

Imagine that thoughts are the branches on a tree. The mind is a monkey that jumps from branch to branch all day long without stopping. As you can imagine, a monkey would get tired from all this jumping… and so do our minds! And when our minds are tired and distracted, they convince us not to do the things we should.

Practicing requires focus because it is deep work. We need to learn to control the inner chatter and calm our minds. Unfortunately, there is no quick fix for internal distractions, it takes time and consistent effort to overcome them.

In part 1 of this performance practice series, we talked about external distractions and how to minimize them. Let’s now talk about different types of thoughts and how we can manage them.

- The Busy Mind

- The Tired Mind

- The Unhelpful Mind

- References

- Coming up Next!

- Let’s stay in touch, join the list!

The Busy Mind

The Busy Mind has lots of thoughts all the time. It loves to make sure we are always thinking about everything we need to do and how we are going to do it (for example, our mind might remind us that we have to do the dishes or that we need to get a birthday present for a friend).

Our minds should not be storage units for to-do lists, schedules, or plans. Our minds should be a place to dream up ideas, be creative, and learn interesting things. And when it comes time to practice we should put all our focus on working on our pieces. So what can we do about it?

Meditation: Focus on your Breath

Stopping the internal chatter before starting to practice is so important! Your practicing will only be effective if your mind is actively involved in the process.

A great way to calm your mind is to spend a few minutes doing meditative breathing before starting to play. You do not have to be a Zen master to practice meditative breathing. Find a quiet place, sit comfortably, set a timer for 5 minutes, close your eyes, and focus your attention on your breath. Notice how the air flows into your body. Feel the breath leave your body as you exhale. If a thought pops into your mind, observe it without interacting with it, and return your focus to your breath.

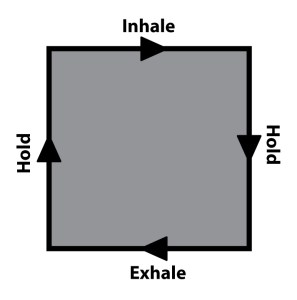

A great technique to try is Square Breathing. Draw a large square on a piece of paper. Place your finger on a corner of the square. Inhale slowly while slowly moving your finger along the side of the square. When you reach the next corner, hold your breath while your finger traces the next side of the square. At the next corner, start exhaling slowly while moving your finger along the third side of the square. At the last corner, hold your exhale while your finger traces the last side and returns to the corner you started on. Repeat the exercise a few times, focusing your mind on your breathing.

Square breathing is a technique I have my students practice, but I tell them to use their piano book instead of a square. As they sit in the audience waiting for their turn to perform, I encourage them to trace the outline of their piano book while breathing.

Students have reported back that it really helped center them before performing. Some commented that they did this exercise when the person right before them was performing. It helped keep them calm when they knew they were up next!

Write it Down: Get those Thoughts out of Your Mind!

It can be enormously frustrating to be playing a passage in your music and suddenly have your mind point out that you need to feed the dog! Your concentration is now gone and you have to bring your mind back to the music, which takes mental energy to do.

An interesting thing happens when we write things down though… the mind stops obsessing over what it wants us to remember! The simple act of writing the thought down puts the mind at ease, frees up mental space, and allows the mind to move onto other thoughts.

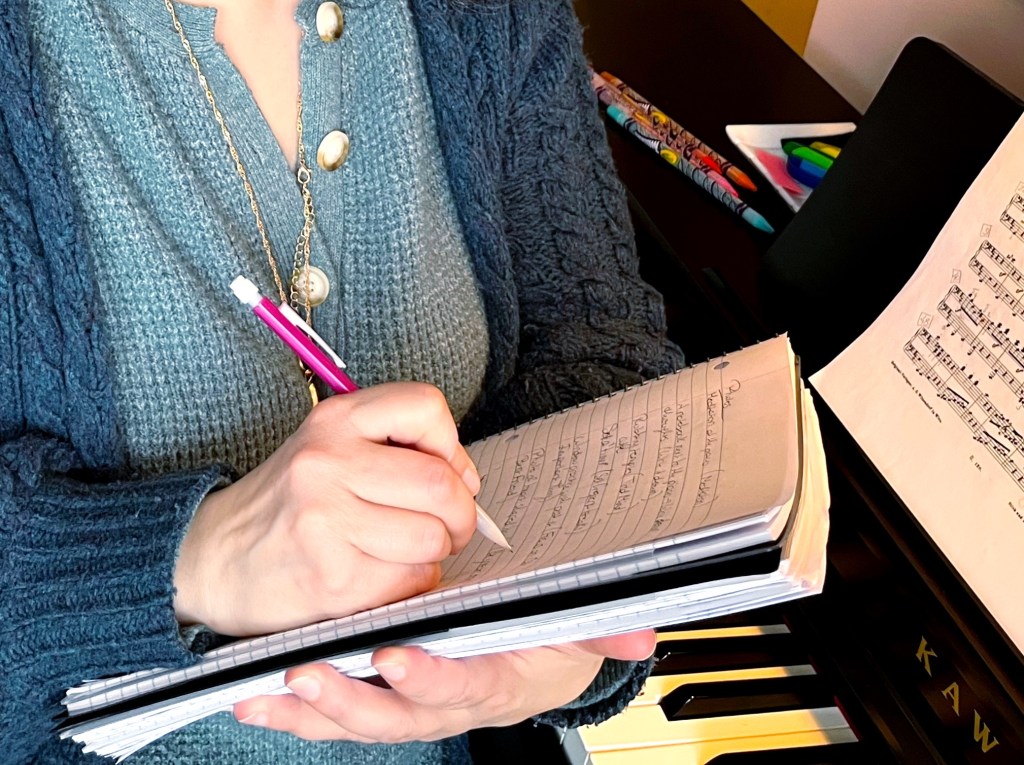

Have a piece of paper or a notebook with you at the piano. Before you begin practicing (or if your mind interrupts you while playing), write down any thought that your mind is trying to help you remember.

Show them the Door: In and Out

When we are focused on work, our minds can often try to distract us by throwing random thoughts into our mental space. From the “I wonder what’s for dinner?” to the “I can’t believe my friend said that!”, the brain is trying to hijack our concentration for a quick thrill (who doesn’t get excited about eating some good food?!).

When these random thoughts pop up, imagine that your mind is a revolving door. The thought comes into your mind and immediately leaves through the other side of the door.

We can watch the thought come and go without focusing our attention on it. This will allow us to continue playing our music without having to re-focus.

The Tired Mind

The Tired Mind has been working hard on intense mental activities. It has run a marathon and now it doesn’t even have energy for a short walk. When we are physically tired, a good night’s rest usually resets our bodies and allows us to wake up with renewed energy. But that may not always be enough when our minds are tired…

A Tired Mind might be more forgetful, stressed, easily distracted, unmotivated to do things, or irritable. When your mind is tired it’s going to try to convince you not to do the things you need to do.

Unfortunately, we can’t always take a mental vacation from our responsibilities, especially when we have a deadline to meet, like an upcoming recital. But we can be gentle and kind to ourselves and still make progress in our practicing even when we don’t feel like playing.

Play Something you Enjoy

Before starting to practice, spend a few minutes just playing music you love! A famous quote states that “Music is a balm for the soul,” it has the power to soothe us and lift our spirits. So play for the pure pleasure of making beautiful music. It will put your mind in a more peaceful, happy, and energized place to start practicing.

Take Frequent Breaks

If we have a lot to work on, it is important to take frequent breaks. A timer is great for this type of practice. Determine how long you want to practice before a break (for example, 20 minutes) and how long each break will be (for example, 10 minutes). Then set the timer and start practicing. When the timer goes off, set a timer for your break period and walk away from the piano. Return to practicing when the timer goes off. Repeat this routine as many times as needed. (I love this cube timer, check out this blogpost for more ways to use it!).

Try it for 5 Minutes

We can do most things if we tell ourselves we’ll only do it for 5 minutes. Sit down at the piano and set a timer for 5 minutes. Play through your recital pieces without stopping for 5 minutes. During that time you will notice parts that need work and parts that you have mastered. When the timer goes off, evaluate how you are feeling. Most times you will feel ok to keep going, so continue to practice, this time working more intentionally on a passage that still needs work. If after the 5 minutes you still feel tired, give yourself grace and walk away from the piano content in knowing that doing something is better than doing nothing at all.

Focus on One Important Thing

If we don’t have a lot of time to practice or our mind is tired, we want to make our practice time as meaningful as possible. Pick something in your piece that is important or that you find difficult (for example, a passage with tricky fingering) and only work on that during your practice time. Your mind will fully focus on this one single task without worrying about having to save time for practicing other things. A lot of progress can be made by just focusing on a single difficulty.

The Unhelpful Mind

The Unhelpful Mind likes to toss negative thoughts into our heads. When we focus on these negative thoughts our minds can quickly escalate the negative self-talk, which oftentimes leads to physical symptoms of anxiety like cold hands, butterflies in the stomach, shaking, heart racing, sweating, stomach pain, etc.

The Unhelpful Mind is exactly that… unhelpful! The thoughts it creates do not help us be better or lead us in the right direction. These thoughts want to see us crash and burn. There are many different categories for these unhelpful thoughts; let’s take a look at a few common ones most musicians hear from time to time:

- Mind-Reading Thoughts – our minds tell us what everyone else is thinking (for example, “Everyone thinks I’m playing terribly!”). We all know that we can’t read other people’s minds, but the Unhelpful Mind likes to try to make you believe that it can.

- Should Thoughts – our minds tell us what we SHOULD be doing to be perfect and the best player ever (for example, “I should be able to play this piece perfectly without a single mistake by now!” or “I should be able to play this because Oliver plays this and we are the same age!”). We all know that there is no such thing as “perfect” but we are still drawn to the idea of perfection like a moth to a flame… We have to avoid the “flame of perfectionism” at all costs because we will never be perfect.

- Overgeneralized Thoughts – our minds tell us something broad (not specific) that it wants us to believe is always true in all situations (for example, “Everyone plays so much better than me! or “I’m never going to get this!”). We know that these thoughts are lies that sneak into our minds when we feel upset, frustrated, or stressed.

- Catastrophic Thoughts – our minds take a small problem (for example, “I’m having a really hard time with this fingering.”) and spirals out of control, turning the small problem into a big one (“I’m going to mess it up at the recital and everyone is going to laugh at me and it’ll be the worst thing to ever happen to me!”)

The Unhelpful Mind can be calmed by using a lot of the same techniques we use to help the Busy Mind and the Tired Mind, like Meditative Breathing, the Revolving Door, and Taking Breaks. But sometimes the Unhelpful Mind can be insistent and we need to take a little extra time and effort to transform the unhelpful thoughts into helpful ones.

Be your own Best Friend

The Unhelpful Mind just told you something negative. Now imagine that your best friend just said those exact words about themselves. When we love someone, we never want to hear them talking badly about themselves. We immediately try to console them, encourage them, and build them up to help them see themselves the way we see them.

We need to show ourselves the same sort of kindness and love that we show our best friends. When an unhelpful thought pops into your mind, talk to yourself like you would talk to your best friend.

Triple R Exercise: Record, Rationalize, and Replace

When an unhelpful thought stops by for a visit, write it down (Record). But don’t only write down the thought itself, write down every detail that was happening when the thought came to you (what you were playing, how you were feeling, anyone who was with you, etc.).

Then, if possible, figure out what kind of thought it was (Rationalize): mind-reading thought, should thought, overgeneralized thought, catastrophic thought, or another type of thought.

Finally, turn that unhelpful thought into a helpful thought (Replace). Talk to someone (a friend, parent, teacher, etc.) if you are having a hard time finding a way to make the thought helpful.

If you find this exercise helpful, keep a notebook at the piano when you practice and draw a table, like the one below, and fill it out as needed.

References

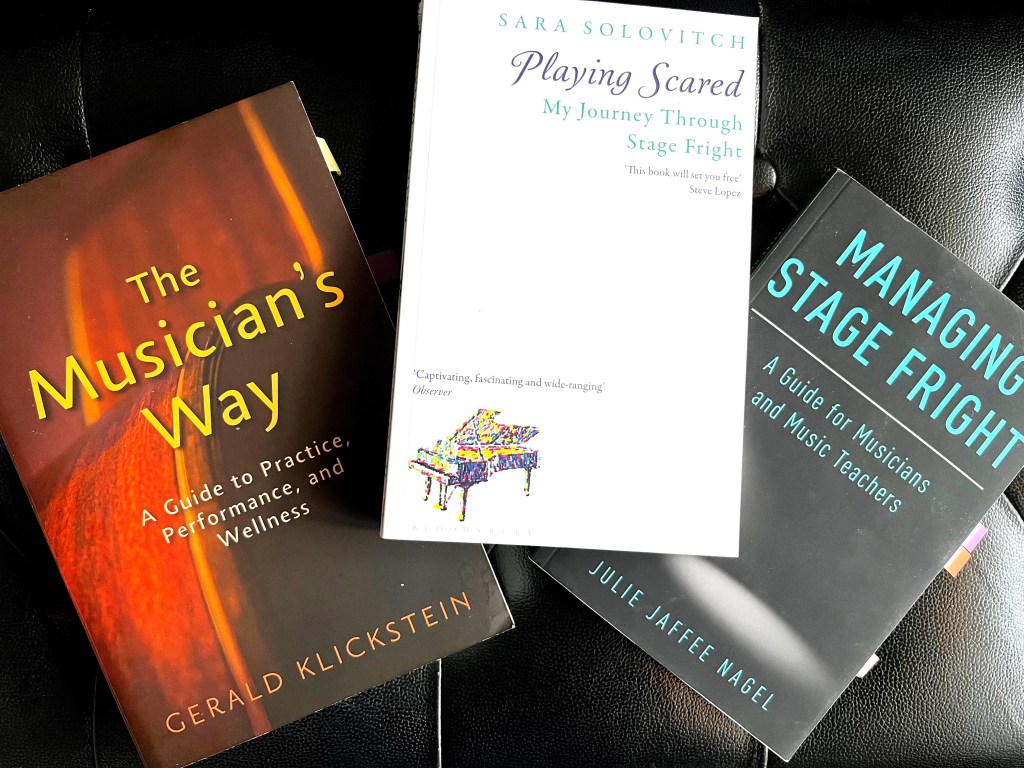

I used many sources for my research and I wanted to take a moment to highlight a few that you may find helpful if you want to dive deeper into the subject:

- The Bulletproof Musician – This website is a treasure trove of information about performance anxiety! Noa Kageyama, a performance psychologist and faculty member of The Julliard School and Cleveland Insitute of Music, offers weekly posts, courses, and a myriad of free resources to help musicians with performance anxiety.

- Managing Stage Fright – A Guide for Musicians and Music Teachers by Julie Jaffee Nagel: This book is filled with practical strategies for managing performance anxiety. The book is directed at teachers, making it unique in the literature. As teachers, we have to navigate the intense emotions students feel when it comes to performing and the author, a pianist and psychoanalyst, conveys her research and strategies in a wonderfully empathetic manner.

- Playing Scared – My Journey through Stage Fright by Sara Solovitch: This is the personal account of the author in achieving her goal of giving a formal recital the day before her 60th birthday. She does research along the way and describes the journeys of famous musicians, actors, athletes, and even a reverend in managing their own stage fright.

- The Musician’s Way – A Guide to Practice, Performance, and Wellness by Gerald Klickstein: This book covers a wide variety of topics. Part II of the book on performance is very informative and provides great practical strategies for musicians to try implementing in their performance practice.

Coming up Next!

In the next post we will be talking about the musical mind and how to focus our attention on what matters while practicing for a performance.

- Performance Practice – Part 1: External Distractions

Recital season brings more than just music—it also brings nerves. While learning a piece is one thing, preparing to perform it confidently in front of an audience requires a different kind of practice. This 4-part series explores strategies to help students manage anxiety, handle distractions, and step onto the stage feeling ready to share their music with confidence. In part 1 we are looking into external distractions. - Slurs & Ladders: The Recital Prep Game

If there is one game my students beg to play year after year (and sometimes when we don’t even have a recital anytime soon!) is this recital prep game. It’s a great de-stressor and it shows students how prepared they are to perform while also injecting some fun and joy back into those recital pieces that may be sounding a little tired. - How to Bow at a Piano Recital

You’ve just finished playing your piano recital pieces and now the audience is clapping, what do you do now??! It’s time to take a bow and enjoy the adulation for all the hard work you put into learning your pieces. Here’s the step-by-step on nailing the perfect piano recital bow! - Positive Notes: Recital Encouragement

Spread some positivity and encouragement to your students this recital season with these adorable Positive Notes! They will help remind them of how hard they work and how much you believe in them.

Let’s stay in touch, join the list!

As a “toucan” of our appreciation download a free set of note flashcards (link in our Welcome email)!

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.