Recital season is upon us and a topic that comes up a lot is performance anxiety. As children get older and become more self-conscious, performance anxiety can start to creep in… It affects everyone (there are countless stories of professional musicians who suffer from performance anxiety) but it doesn’t always affect everyone in the same way or even negatively. It can be harnessed as an agent of good to enhance their performance.

As pianists we do not always have the luxury of numbers (like other instruments playing in orchestras or bands) and it can feel overwhelming to sit in front of an audience to perform (even if it’s a wonderfully friendly audience made up of family and friends). This is an extremely important topic to work on with students but oftentimes gets overlooked because of the more “pressing” matter of working out the technical difficulties of the performance pieces (and I’ve been guilty of this too!).

In this four part series, I’m going to talk about how students can practice for performance.

But isn’t practicing for a performance just playing the piece from beginning to end like one would on the day of the recital? As we will see, the answer is a resounding no.

The type of practice most students are familiar with is used to learn the piece. Through this type of practice, the student works out the technical difficulties, gains consistency and ease in playing it, increases accuracy and expression. Then when they are “done learning”, they are able play the piece. But this is not enough to perform the piece with confidence in a high-stakes setting like a recital or audition.

Performance practice requires a different set of practice strategies. The suggested strategies in this series are based on research but obviously not everything works for everyone. Students should experiment with all the different strategies to find the best ones that work for them. But, all of these strategies take time and consistent effort to make them useful… They require practice.

As teachers we want our students to approach the piano at the recital feeling confident and ready to share their music with the audience. The performance practice strategies will help prepare students for things that may happen on the day of the recital… intrusive thoughts, performance anxiety, and unexpected and unwelcome distractions. When students have a sense of control over the “unexpected” and are equipped with tools to handle them, they are free to play in the moment with confidence. They have practiced for performance and they know what to do!

- References

- What are External Distractions?

- Types of External Distractions and Management Methods

- Spot the Distractions: What’s Stealing your Focus?

- Coming up next!

- Let’s stay in touch, join the list!

References

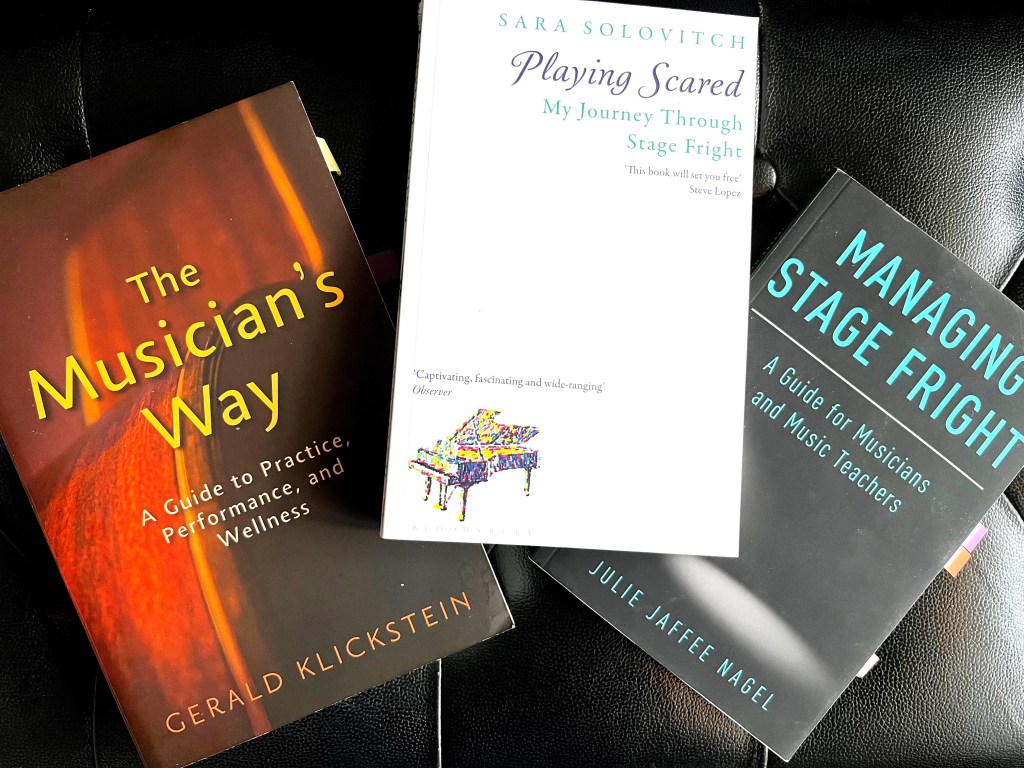

I used many sources for my research and I wanted to take a moment to highlight a few that you may find helpful if you want to dive deeper into the subject:

- The Bulletproof Musician – This website is a treasure trove of information about performance anxiety! Noa Kageyama, a performance psychologist and faculty member of The Julliard School and Cleveland Insitute of Music, offers weekly posts, courses, and a myriad of free resources to help musicians with performance anxiety.

- Managing Stage Fright – A Guide for Musicians and Music Teachers by Julie Jaffee Nagel: This book is filled with practical strategies for managing performance anxiety. The book is directed at teachers, making it unique in the literature. As teachers, we have to navigate the intense emotions students feel when it comes to performing and the author, a pianist and psychoanalyst, conveys her research and strategies in a wonderfully empathetic manner.

- Playing Scared – My Journey through Stage Fright by Sara Solovitch: This is the personal account of the author in achieving her goal of giving a formal recital the day before her 60th birthday. She does research along the way and describes the journeys of famous musicians, actors, athletes, and even a reverend in managing their own stage fright.

- The Musician’s Way – A Guide to Practice, Performance, and Wellness by Gerald Klickstein: This book covers a wide variety of topics. Part II of the book on performance is very informative and provides great practical strategies for musicians to try implementing in their performance practice.

What are External Distractions?

As students prepare for their recital performance, they may be facing lots of external distractions when they sit down to practice (or maybe even ones that prevent them from practicing altogether!).

An external distraction is something that comes from the outside (not from within you) that takes your attention away from what you are doing.

Everyone is surrounded by external distractions… devices, pets, siblings, children, parents, friends and SO much more! It can often feel like the world around us is constantly trying to distract us from what we really need to do. Our students face the same challenges.

Learning a new piece and preparing it for performance takes a lot of focused work. Winning the battle against external distractions may seem challenging but it’s well worth the effort!

It all starts by removing the distractions students can control AND coming up with a plan to handle the distractions they can’t control.

Although it is important for students to be able to play through the occasional unintended noise during a performance (we’ll talk about that in a later post), for the hard work of learning their recital pieces, students should work in a space where external distractions are minimal.

By learning to protect their focus from everyday distractions, students set themselves up for productive practice sessions while also strengthening their ability to stay focused in any setting.

Types of External Distractions and Management Methods

Let’s talk about four of the most common external distractions that students may run into and different strategies for students to handle them.

Distraction no. 1 – Electronics

I think this is the one most students struggle with… The brain LOVES electronics because they stimulate the brain without the brain having to do any real work. They are instant gratification suppliers and the brain eats it up! Children and teens are particularly susceptible to their siren call. Some of the most common culprits are smartphones, smartwatches, tablets, videogames, computers, and the television.

Here are five suggestions to protect practice time from electronics:

- Put the device in another room.

- Put the device in Airplane mode.

- Turn off notifications.

- Turn off the device.

- Use these distractions as rewards for practicing.

With electronics, the easiest method is distance. Students may think about their electronics during practice, but if the device is out of reach, they’ll be less tempted to stop.

Distraction no. 2 – People

Our friends and family mean well, but sometimes they can unintentionally distract us from our practicing. Most of the time parents will be so delighted that their child is practicing that they will not interrupt them (unless there is a real reason). The true culprits are usually siblings and friends.

In order to handle these distractions, a student could:

- Let everyone in the house know that they are practicing and don’t want to be disturbed.

- Practice when siblings are not home (for example, their sister is at a dance class).

- Ask siblings to do their activities in a different room of the house (this may require parental intervention).

- Set aside a specific time to answer texts or FaceTime friends (a student could even go so far as to let friends know that they are practicing and will only be available at after a specified time).

Usually a conversation is enough to get these external distractions under control.

Distraction no. 3 – Practice Space

A student’s practice space should have everything they need for a successful practice session, which could include but is not limited to their instrument, their instrument’s accessories, proper lighting, comfortable ambient temperature, metronome, and a pencil.

To set themselves up for success a student could:

- Make sure their instrument is always ready for practicing (tuned, not convered in clutter, etc.).

- Keep everything they need at their instrument (sheet music, metronome, pencil, timer, etc.).

- Make sure their space is well-lit, whether with natural or artificial light.

- Make sure they are comfortable (wear clothing that is season appropriate so they are not too hot or too cold, ensure that their outfit is not restrictive and allows them to move freely while wearing it, etc.).

If the practice space is ready to go without the need to tidy up or move things around, it’s easier to just slip into practice mode. Taking a few minutes at the end of practice to reset the space makes the next session easier to start.

Distraction no. 4 – Noise

As musicians our sense of hearing is extremely important! Our ears need to focus on the music we are practicing. Students in particular are still developing their listening ear so external noise is even more problematic.

Noise can come from every source imaginable… pets, siblings, background house noise, conversations, neighborhood noise, devices, etc.

In order to keep focused and not be distracted by external noise sources, students can:

- Use headphones while practicing (if they are using a digital piano).

- Put pets in a different room.

- Ask family members to use their devices in a different room.

- Turn off machines that generate a lot of noise (dishwashers, fans, robot vacuums, etc.).

Spot the Distractions: What’s Stealing your Focus?

Last year, when my students and I worked through this four part performance practice series, they occasionally had a little extra homework beyond the performance practice strategies. Since external distractions are something students can easily recognize, the following activity empowers them to take control of their practice environment by identifying and addressing the specific distractions that interfere with their focus.

We drew a table and labeled the columns:

- External distraction – If the student identified an external distraction, they would describe it here.

- How did you manage the distraction? – The student would then explain what they did to eliminate/minimize the distraction or refocus on practicing (if the external distraction was beyond their control).

- Did it work? – A simple yes or no answer.

It was very interesting to see the variety of distractions my students were facing (every home is different!) and the creative solutions they came up with to handle them. I was very proud of them!

Coming up next!

In the next post we will be talking about internal distractions – thoughts that pop into our heads – and strategies to calm the inner chatter and refocus our minds.

- Slurs & Ladders: The Recital Prep Game

If there is one game my students beg to play year after year (and sometimes when we don’t even have a recital anytime soon!) is this recital prep game. It’s a great de-stressor and it shows students how prepared they are to perform while also injecting some fun and joy back into those recital pieces that may be sounding a little tired. - How to Bow at a Piano Recital

You’ve just finished playing your piano recital pieces and now the audience is clapping, what do you do now??! It’s time to take a bow and enjoy the adulation for all the hard work you put into learning your pieces. Here’s the step-by-step on nailing the perfect piano recital bow! - Positive Notes: Recital Encouragement

Spread some positivity and encouragement to your students this recital season with these adorable Positive Notes! They will help remind them of how hard they work and how much you believe in them.

Let’s stay in touch, join the list!

As a “toucan” of our appreciation download a free set of note flashcards (link in our Welcome email)!

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.